The Soulbury Pumphouse and Canal Trail

|

Places of Interest

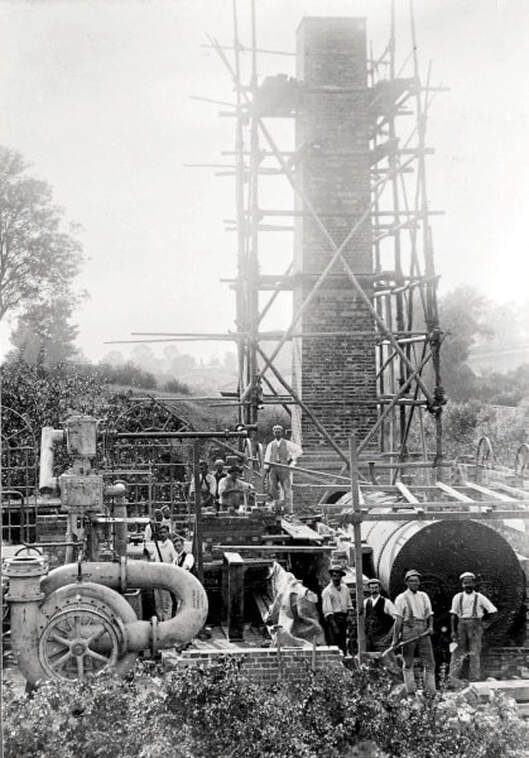

SOULBURY PUMPHOUSE When a boat passes down a lock it takes a lot of water downstream with it. Unless that water is replaced the canal would eventually dry out. When the Grand Junction Canal, which would later become the Grand Union, opened in 1800 a series of reservoirs were built to collect water from streams and rivers. These reservoirs were used to keep the water levels high enough for boats to stay afloat. But if there were a lot of boats using the locks, or there was a drought, these water supplies could dry up and traffic would be brought to a standstill. In 1838, the canal company decided they needed to solve this problem and commissioned the engineering firm Grissell and Peto, who also built Nelson’s Column and the Houses of Parliament, to find a way to move the water back up the hill. A series of nine pumphouses like this one at Three Locks, known as ‘the Northern Engines’, were operational by 1841. Each housed a steam powered pump that drew water up from below the lock and pumped it through a tunnel, back to above the lock where it had come from. The pumphouse is a simple rectangular building but with some decorative design elements such as the semi-circular radiating fanlight above the door and the ornamental glazing bars on the windows. The building was listed at Grade II in 1984 and more recently renovated by the Canal & River Trust, in partnership with National Lottery Heritage Fund and opened to the public in 2019. |

|

SOULBURY LOCKS

All of today’s lock gates follow a design by Leonardo Da Vinci that uses a mitred, 45 degree angle, where the gates meet, which uses the difference in water pressure on either side of the gate to force them closed as the water levels are changed to lift or lower the boat inside. Every lock on the canal, like every bridge, has its own number, starting with No. 1 at Braunston, 42 miles north of here, where the Grand Union Canal joins the Oxford Canal. The flight of three locks at Soulbury, Nos. 24, 25 and 26, take the canal 6m (20ft) further uphill from its lowest stretch across the Ouse Valley in Milton Keynes up to Tring summit at 121m (395ft) above sea level. As well as using the pumphouse to return water upstream the locks at Soulbury also have side ponds. These were used to capture some of the water that would otherwise be lost downstream when the lock was emptied. When the lock was refilled to allow the passage of the next boat the water in the pond could be used instead of filling the whole lock from above. Although these water-saving devices are no longer in use they, and their sluice gate gear, are still clearly visible alongside the towpath. |

THE THREE LOCKS PUBLIC HOUSE

When canal boats were horse drawn, the canalside inn was a recognized tying up point, where animals could be stabled and the workers refreshed. They might also be used as an exchange point for horses when long distance journeys were undertaken. The Three Locks was purpose built as a canalside pub, and was originally known as The New Inn until the mid-twentieth century. Census records from 1881 list the innkeeper as Mary Faulkner who ran the pub with her two servants, Charles Barron and Mary Curtis. On the night of the census the inn had one guest, Joseph Staige, a retired optician from Birmingham who was perhaps stopping off overnight on his way home from London on a flyboat. The building just to the south of the pub is Three Locks Cottage, which was originally the lock keeper’s cottage. Lock keepers were responsible for the smooth running of the boats through the locks and to make sure that the water supply was conserved: if levels were low the keeper would close the lock to traffic until the supply had recovered. The canal still has lock keepers but they are now mostly volunteers and mostly live off site.

When canal boats were horse drawn, the canalside inn was a recognized tying up point, where animals could be stabled and the workers refreshed. They might also be used as an exchange point for horses when long distance journeys were undertaken. The Three Locks was purpose built as a canalside pub, and was originally known as The New Inn until the mid-twentieth century. Census records from 1881 list the innkeeper as Mary Faulkner who ran the pub with her two servants, Charles Barron and Mary Curtis. On the night of the census the inn had one guest, Joseph Staige, a retired optician from Birmingham who was perhaps stopping off overnight on his way home from London on a flyboat. The building just to the south of the pub is Three Locks Cottage, which was originally the lock keeper’s cottage. Lock keepers were responsible for the smooth running of the boats through the locks and to make sure that the water supply was conserved: if levels were low the keeper would close the lock to traffic until the supply had recovered. The canal still has lock keepers but they are now mostly volunteers and mostly live off site.

|

STOKE HAMMOND PUMPHOUSE

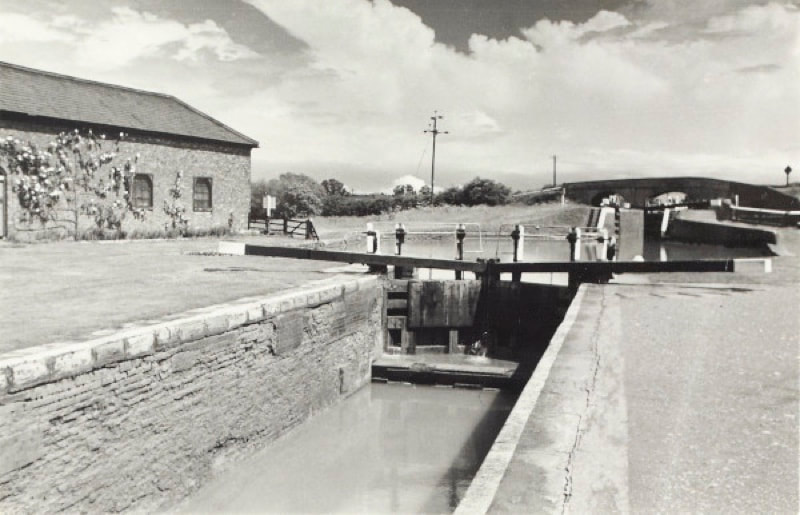

The Stoke Hammond pumphouse, another of the Northern Engines, has retained its distinctive fanlight and decorative windows but like its the Soulbury pumphouse it has also lost the chimney associated with the steam engine that powered the pump. Only one pumphouse on this stretch of canal retains its chimney, at Seabrook, ten miles to the south of Three Locks. The building opposite the pumphouse was once a lock keeper’s cottage and the lock, No. 23, has a rise of 3.5m (12ft). The bridge here, No. 104, is also listed, no doubt partly because of its unusual second arch. The Grand Junction Canal Company found they could save water, and time, if they built narrower locks which could carry smaller boats up and down but use less water than the original double width locks. These duplicate locks have since been filled in but the second arch of the bridge here at Stoke Hammond indicates the line of the approach to the infilled lock. |

BLETCHLEY LAKES ESTATE

The Lakes Estate was the last London 'overspill' estate to be built in Bletchley. It was jointly funded by Bletchley Urban District Council and the Greater London Council. In October 1966 an exhibition was held at Wilton Hall in Bletchley, presenting to local residents what was then known as 'the Water Eaton scheme' as it extended southwards from the old village of Water Eaton. The council decided at a meeting in January 1967 that the streets of the Water Eaton estate would be named after Lakes. The designs for the Lakes housing were very different from that in the rest of Bletchley. The houses had flat roofs - a feature that it was believed would allow as many of the residents as possible to have a view of Brickhills that can be seen across the valley to the East.

Another earlier example of London overspill development, the Trees estate, can be seen in front of the Lakes estate a little further along the canal and runs all the way from Water Eaton into Fenny Stratford. Due to the shortage of manpower immediately after the war, Italian prisoners-of-war were used in the building of these houses. In between the Lakes and the Trees are the more modern houses of the Waterside development.

The Lakes Estate was the last London 'overspill' estate to be built in Bletchley. It was jointly funded by Bletchley Urban District Council and the Greater London Council. In October 1966 an exhibition was held at Wilton Hall in Bletchley, presenting to local residents what was then known as 'the Water Eaton scheme' as it extended southwards from the old village of Water Eaton. The council decided at a meeting in January 1967 that the streets of the Water Eaton estate would be named after Lakes. The designs for the Lakes housing were very different from that in the rest of Bletchley. The houses had flat roofs - a feature that it was believed would allow as many of the residents as possible to have a view of Brickhills that can be seen across the valley to the East.

Another earlier example of London overspill development, the Trees estate, can be seen in front of the Lakes estate a little further along the canal and runs all the way from Water Eaton into Fenny Stratford. Due to the shortage of manpower immediately after the war, Italian prisoners-of-war were used in the building of these houses. In between the Lakes and the Trees are the more modern houses of the Waterside development.

|

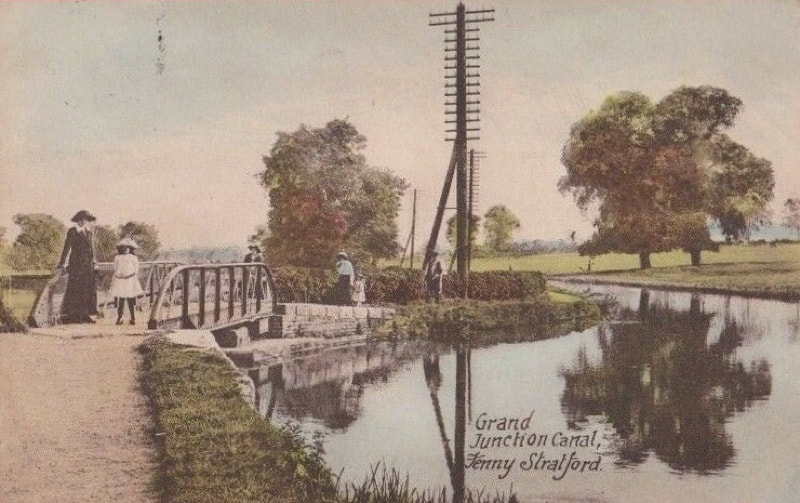

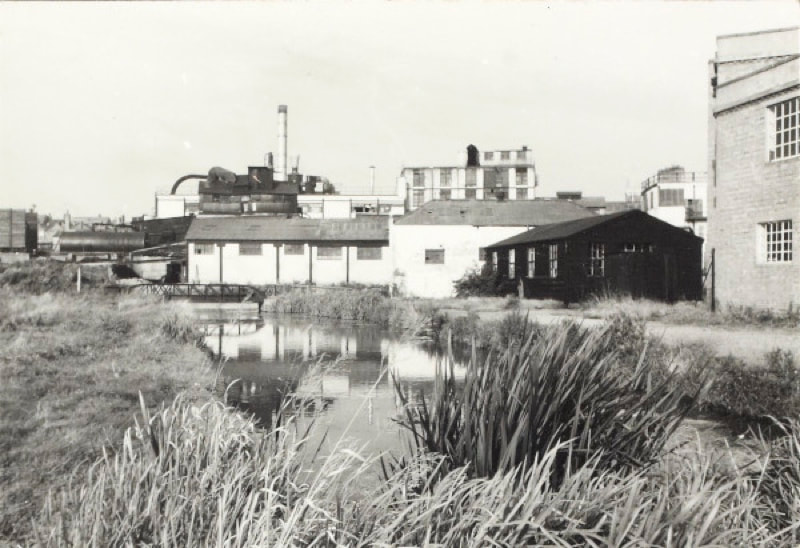

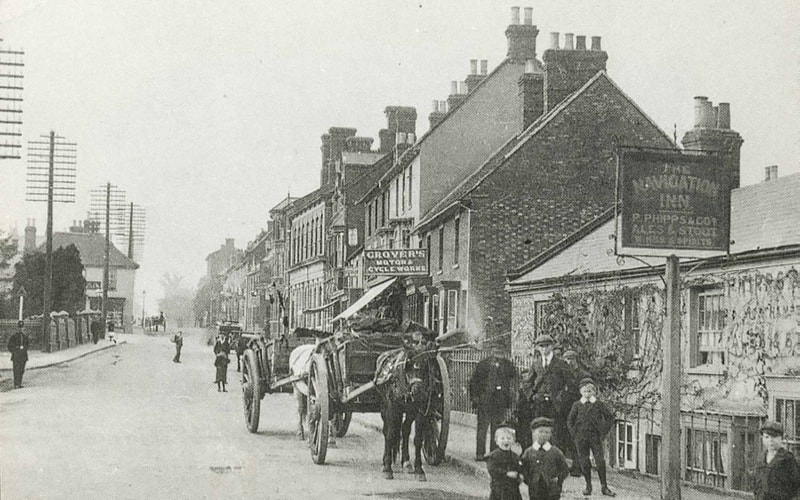

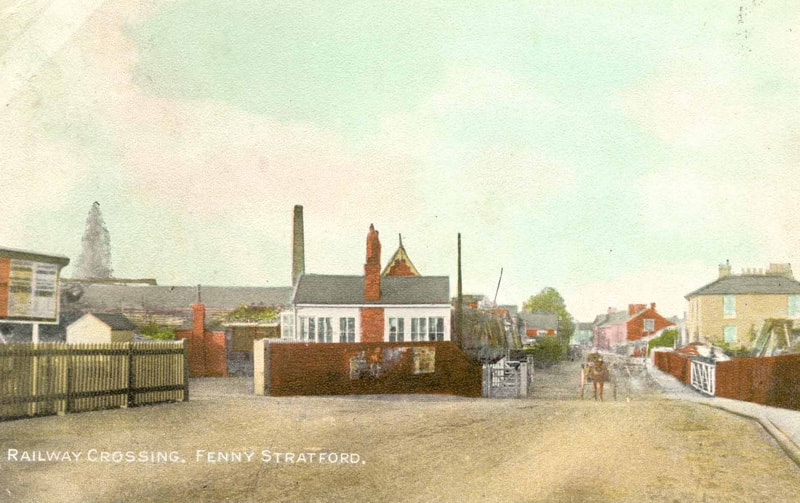

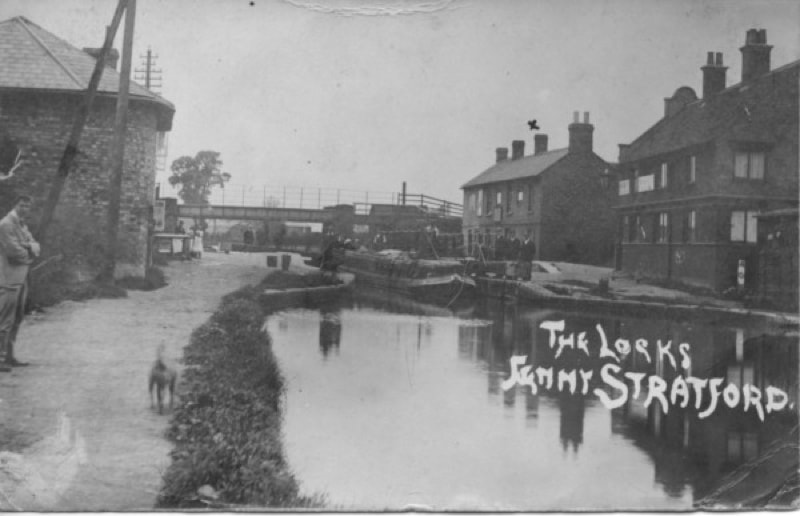

FENNY STRATFORD WHARF

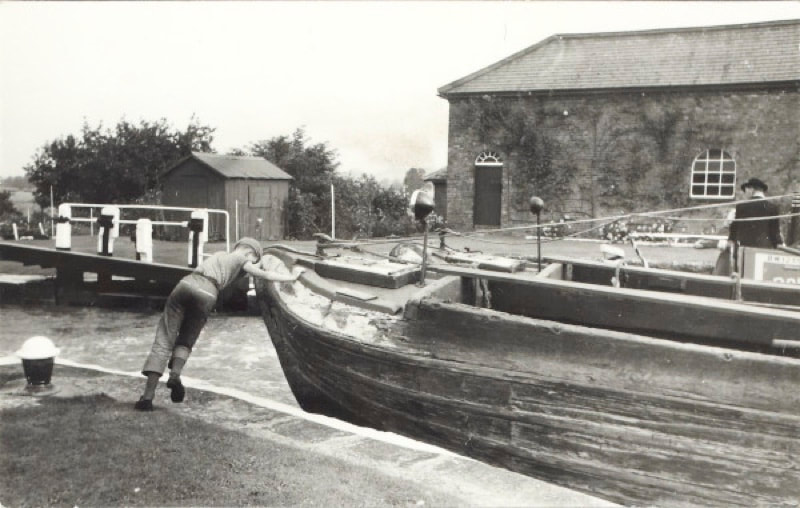

The houses alongside the canal at Fenny Stratford are built on the site of a brick kiln and a wharf which was used to load, among other things, bricks and coal from barges. The towpath was carried over the entrance to the wharf by a swingbridge, shown in the photographs above, which has since been replaced by the current liftbridge. There would have been wharves like this all along the canal, providing a transport network between the nation’s industries and the towns they served. At Fenny Stratford there was also a sugar refinery on the opposite bank, which had its own mechanism for unloading raw grain and carrying its products (treacle, molasses and sugar) to its customers. The canal was also useful as a corridor for other kinds of communication. Large telegraph poles followed the waterway out of London and at Fenny Stratford they linked to the GPO repeater station. Here the signal was amplified for the next stage of its journey north or, during World War 2, to the code-breakers at Bletchley Park. |

|

WATLING STREET

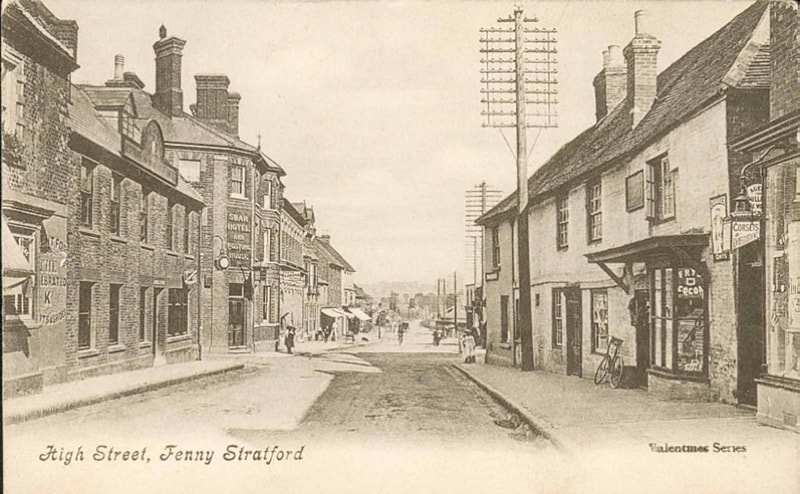

Bridge 96 takes the canal beneath the old Roman road of Watling Street. Fenny Stratford has a long history tracing back through the Roman settlement of Magiovinium, located just outside the current town centre. A gold coin dating from the Iron Age and a hoard of Roman silver denarii were discovered in the vicinity. More recently the town was granted a market charter in the 13th century and, having survived the ravages of the Great Plague in 1665, became a thriving coaching town in the late 18th century. Traffic from London brought prosperity which was further enhanced with the arrival of the Grand Junction Canal in 1800. Between 1750 and 1810 there were 40 alehouses and coaching houses recorded in the town. |

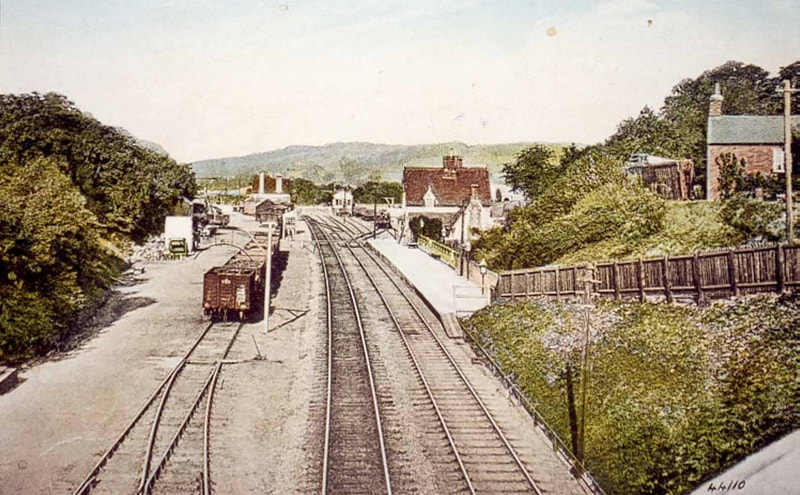

RAILWAY BRIDGE

The history of canals is intrinsically linked with the history of the railways. Canal companies, seeing the threat posed by this faster mode of transport, strongly opposed the building of railways, especially as they followed similar routes and took advantage of the same geographical features to cross valleys and cut through hills.

Railway lines often needed bridges to take them over existing canals and here at Fenny Stratford the Stephensons’ branch line eastwards from Bletchley to Bedford opened in 1846. The route later expanded and became known as the ‘Varsity line, linking the university cities of Oxford and Cambridge. The advent of the railways quickly made the stagecoaches, which plied their trade along Watling Street through Fenny Stratford, obsolete. The demise of canal haulage as a viable business followed shortly, despite the efforts of the newly formed Grand Union Canal Company in the 1930s to promote the benefits of its modernised, but still comparatively sedate, freight network. In 1968, the Transport Act officially recognised the leisure value of canals. Since then they have been owned and managed by Canal & River Trust (formerly British Waterways). Canal & River Trust's role is to look after and bring to life the waterway network - promoting the wellbeing of people who live near or visit our canals.

The history of canals is intrinsically linked with the history of the railways. Canal companies, seeing the threat posed by this faster mode of transport, strongly opposed the building of railways, especially as they followed similar routes and took advantage of the same geographical features to cross valleys and cut through hills.

Railway lines often needed bridges to take them over existing canals and here at Fenny Stratford the Stephensons’ branch line eastwards from Bletchley to Bedford opened in 1846. The route later expanded and became known as the ‘Varsity line, linking the university cities of Oxford and Cambridge. The advent of the railways quickly made the stagecoaches, which plied their trade along Watling Street through Fenny Stratford, obsolete. The demise of canal haulage as a viable business followed shortly, despite the efforts of the newly formed Grand Union Canal Company in the 1930s to promote the benefits of its modernised, but still comparatively sedate, freight network. In 1968, the Transport Act officially recognised the leisure value of canals. Since then they have been owned and managed by Canal & River Trust (formerly British Waterways). Canal & River Trust's role is to look after and bring to life the waterway network - promoting the wellbeing of people who live near or visit our canals.

|

FENNY STRATFORD LOCK

The lock at Fenny Stratford is the first lock that raises the level of the canal after it has crossed the long flat plain of the Ouse Valley. The rise of this lock though is only very small, just 28cm (11 inches). In contrast to the other locks in the area this lock was not built to raise or lower boats. Instead, the small difference in height here meant that the water level was dropped to below where the leaks were in the channel. Also here at Fenny Stratford is another pumphouse of the Northern Engines, the Red Lion canalside pub, and a collection of workers’ cottages. A well preserved swingbridge provides a connection between the towpath, the Red Lion and the town of Fenny Stratford beyond. |

The Soulbury Pumphouse trail and associated elements were funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund and created by Living Archive MK.